Classical music in the Mughal India

Background:

- Another branch of cultural life in which Hindus and Muslims cooperated was music. Indian music had established itself in the court circles of the Sultanat during the fourteenth century, and even an orthodox ruler like Firuz Tughlaq had patronized music. selfstudyhistory.com

- The development of music in North India was largely inspired and sustained by the bhakti movement.

- Many of the writings of the bhakti saints were set to different ragas and surs.

- The compositions of the 16th and 17th century saint poets were invariably set to music.

- In Vrindavan, Swami Haridas promoted music in a big way. Akbar himself is supposed to have gone incognito to hear his music. He is also considered to be the teacher of the famous Tansen of Akbar’s court.

- Centres of musical study and practice were mainly located in regional kingdoms. The rulers of the provincial kingdoms during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were great patrons of music.

- Raja Man Singh of Gwaliyar (1486-1517) was himself a skilled musician and a patron of musicians.

- He is credited with creating many new melodies which were collected in a work, Man Kautuhal.

- He played a distinguished part in the growth and perfection of Dhrupad, a variant style of the North Indian music.

- Raja Man Singh of Gwaliyar (1486-1517) was himself a skilled musician and a patron of musicians.

- Thus patronage to music was given at the courts, temples and sufi gatherings.

- Among the rulers of Delhi, Adali, son of Islam Shah Sur, was a great patron of music and was an accomplished player of pakhawaj.

Under Akbar

- Like Babur, Akbar was also fond of music.

- The Ain-i-Akbari, written by Abu’l-Fazl suggests that there were 36 musicians of high grate in the Mughal court of Akbar.

- It mentioned two bin players native to Gwalior, Shihab Khan and Purbin Khan.

- Akbar himself was a learned musician.

- He further studied Hindu vocalization under Lal Kalawant who taught him “every breathing and sound that appertains to the Hindi language.”

- Abul Fazl tells us that Akbar was very fond of music from his early years. He says:

- “His Majesty has such a knowledge of the science of music as trained musicians do not possess; and he is likewise an excellent hand in performing especially on the nagara.”

- It was due to his interest in music that Akbar took over the services of Tansen from Man Singh.

- Another famous musician was Baba Ram Das. He seems to have been attached to Bairam Khan.

- Sur Das, son of the celebrated singer Ram Das and one of the greatest Hindi poets of all times, was also a musician of Akbar’s court.

- The emperor’s interest in and patronage of music led to great progress in the instrumental as well as the vocal art. At his court Hindu and Muslim music mingled and became one.

- In the fort at Fatehpur Sikri, a pond was built with a small island in the middle, where musical performances were given.

- Akbar patronised celebrated musician Tansen in his court and he was credited with invention of Raga Deepak.

- Tansen is considered one of the great exponents of North Indian system of music.

- The style of singing which he took from Gwaliyar was the stately drupad style.

- He is given credited for introducing some famous ragas viz., Miyan ki Malhar, Miyan ki Todi, Mian ki Mand, Mian ka Sarang and Darbari.

- Several of these raga compositions have become mainstays of the Hindustani tradition.

- He is the creator of major ragas like Darbari Kanada, Darbari Todi, and Rageshwari.

- Tansen also authored Sangeeta Sara and Rajmala which constitute important documents on music.

- Ali Khan Karori is one of the rare musicians – along with the illustrious singer-composer Tansen to have been the subject of an individual portrait.

Portrait of Naubat Khan Kalawant by Mansur

Tansen:

- Mian Tansen (born 1493 as Ramtanu Pandey – died 1586) was a prominent Hindustani classical music composer, musician and vocalist, known for a large number of compositions, and also an instrumentalist who popularised and improved the plucked rabab (of Central Asian origin).

- At some point, he was discipled for some time to Swami Haridas, the legendary composer from Vrindavan and part of the stellar Gwalior court of Raja Man Singh Tomar (1486–1516 AD), specialising in the Dhrupad style of singing.

- His talent was recognised early and it was the ruler of Gwalior who conferred upon the maestro the honorific title ‘Tansen’.

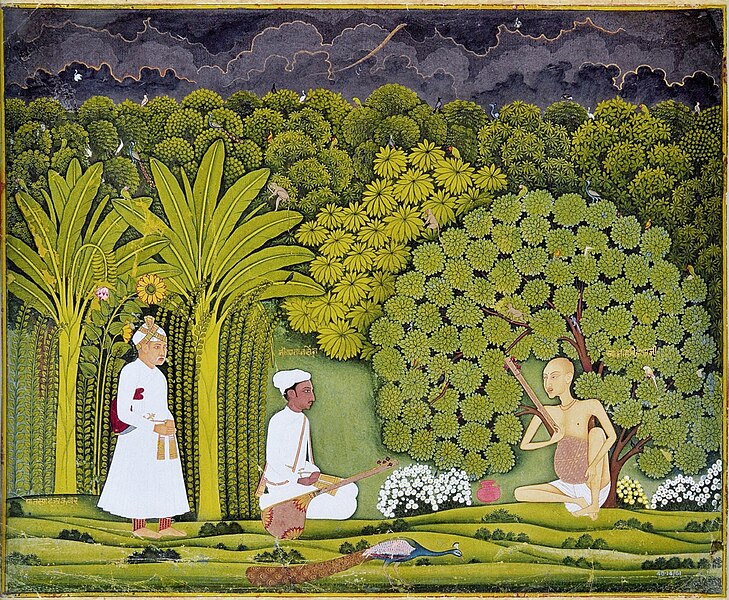

Akbar watching as Tansen receives a lesson from Swami Haridas. Imaginary situation depicted in Mughal miniature painting (Rajasthani style, 1750 AD) - From Haridas, Tansen acquired not only his love for dhrupad but also his interest in compositions in the local language.

- This was the time when the Bhakti tradition was fomenting a shift from Sanskrit to the local idiom (Brajbhasaand Hindi).

- He was among the Navaratnas (nine jewels) at the court of the Mughal EmperorJalal ud-din Akbar. Akbar gave him the title Mian, an honorific, meaning learned man.

- Tansen became the leading singer at the court of Akbar.

- Tansen composed many songs in Hindi and created new ragas many of which are sung even to-day.

- The style of singing which he took from Gwaliyar was the stately drupad style.

- The presence of musicians like Tansen in Akbar’s court has been related to the theoretical position of making the empire’s audible presence felt among the population, a mechanism related to Naubat or ritual performance.

- The fort at Fatehpur Sikri is strongly associated with Tansen’s tenure at Akbar’s court.

- Near the emperor’s chambers, a pond was built with a small island in the middle, where musical performances were given. Today, this tank, called Anup Talao.

- The legendary musical prowess of Tansen surpasses all other legends in Indian music. In terms of influence, he can be compared to the prolific Sufi composer Amir Khusro (1253–1325), or to Bhakti tradition composers such as Swami Haridas.

- Several of his raga compositions have become mainstays of the Hindustani tradition, and these are often prefaced with Mian ki, e.g. Mian ki Todi, Mian ki Malhar, Mian ki Mand, Mian ka Sarang; in addition he is the creator of major ragas like Darbari Kanada, Darbari Todi, and Rageshwari.

- Tansen also authored Sangeeta Sara and Rajmala which constitute important documents on music.

- His influence was central to creating the Hindustani classical ethos as we know today. Almost all gharanas of Hindustani classical music claim some connection with the Tansen lineage though some try to go further back to Amir Khusro.

- The Dhrupad style of singing, this was formalised essentially through the practice by composers like Tansen and Haridas, as well as others like Baiju Bawra who may have been a contemporary.

- After Tansen, some of the ideas from the rabab were fused with the traditional Indian stringed instrument, veena; one of the results of this fusion is the instrument sarod, which does not have frets and is popular today because of its perceived closeness to the vocal style.

- The famous qawwals is claimed to be lineage from Mian Tansen though many consider it wrong.

- Tansen was buried in the mausoleum complex of his Sufi master Shaikh Muhammad Ghaus in Gwalior. According to legend, Tansen’s son Bilas Khan, in his grief, composed Bilaskhani Todi.(Bilaskhani Todi is a Hindustani classical raga. It is a blend of the ragas Asavari and Todi).

Under Shahjahan

- He was also a patron of music and himself a singer.

- There is a reference that his voice was so melodious that Sufi saints became emotional.

Under Aurangzeb

- Aurangzeb himself was an accomplished player of the veena, and patronised music during the first ten years of his reign.

- But growing puritanism and a false sense of economy made him banish the singers from his court.

- Instrumental music however continued.

- Despite Aurangzeb’s jibe to the protesting musicians to bury music deep, Aurangzeb’s reign saw the production of a large number of books on music.

- The most famous of these was Tuhfat-ul-Hind written for Aurangzeb’s grandson, Jahandar Shah.

- Members of the royal family including ladies in the haram and many nobles continued to patronise music.

In 18th Century

- In the 18th century, music in North Indian style received great encouragement at the court of the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah.

- His most famous singers were Sadarang and Adarang. They were masters of dhrupad but also trained many pupils in the Khayal style of music which was considered more lyrical in theme and erotic in approach. This greatly enhanced its popularity.

- Muhammad Shah himself composed Khayals under the pen-name Rangila Piya.

- Many courtesans also became famous for their music and dance.

- Several new forms of music such as Tarana, Dadra and Ghazal also came into existence at this time.

- Tabla and sitar became popular during this period.

- Moreover, some folk forms of music were also incorporated in the courtly music.

- In this category mention may be made of Thumri, employing folk scales, and to Tappa developed from the songs of camel drivers of Punjab.

- Later Mughal kings continued to patronise music but slowly it declined with the decline of Mughals but development of the composite culture in the field of music during Mughals is still visible in Indian classical music like Hindustani music.

In 19th Century

- In the beginning of the 19th century, the British colonisers and the affluent Anglo-Indians got into the habit of commissioning local painters to execute a series of portraits in a Western style – eventually giving life to a movement called the “Company School”.

- Among the subjects painted featured musicians and courtisans of the time.

- The Anglo-Indian Colonel James Skinner was one of the influential figures of Delhi and kept musicians and dancers in his house.

- He commissioned a renowned artist to create an album which featured the portrait of a blind binkar, Miyan Himmat Khan Kalawant.

- His title Kalawant – exclusively reserved for dhrupad singers and bin players – nonetheless indicates that he belonged to the highest echelons of professional musicians.

While in the South the texts of music enforced a stricter science, in the North the absence of texts permitted greater liberty. There were thus several experiments in mixing the ragas carried out in the North. A loose code-of North India style of music is a feature that has continued to the present day.

In South India

- In the South, a system of parent and derivative modes, i.e., Janaka and Janya ragas, existed around the middle of the 16th century.

- The earliest treatise which deals with this system is titled Swaramela Kalanldhi.

- It was written by Ramamatya of Kondavidu (Andhra Pradesh) in 1550.

- It describes 20 janak and 64 janya ragas.

- The earliest treatise which deals with this system is titled Swaramela Kalanldhi.

- Later, in 1609, one Somanatha wrote Ragavibodha in which he incorporated some concepts of the North Indian style.

- It was sometimes in the middle of the 17th century that a famous treatise on music, called Caturdandi-prakasika was composed by Venkatamakhin in Thanjavur (c. 1650).

- The system propounded in the text has come to form the bedrock of the Carnatic system of music.

==========================================================================

Hindustani School of Music

Historical development:

- Hindustani classical music is the Hindustani or North Indian style of Indian classical music found throughout Eastern Pakistan and North India.

- The style is sometimes called North Indian classical music or Shastriya Sangit.

- It is a tradition that originated in Vedic ritual chants and has been evolving since the 12th century CE, in North India.

- It is traditional for performers who have reached a distinguished level of achievement to be awarded titles of respect; Hindus are usually referred to as pandit and Muslims as ustad.

- An aspect of Hindustani music going back to Sufi times is the tradition of religious neutrality: Muslim ustads may sing compositions in praise of Hindu deities, and vice versa.

- Around the 12th century, Hindustani classical music diverged from what eventually came to be identified as Carnatic classical music.

- The central notion in both these systems is that of a melodic mode or raga, sung to a rhythmic cycle or tala.

- The tradition dates back to the ancient Samaveda, (sama meaning “song”), which deals with the norms for chanting of srutis or hymns such as the Rig Veda.

- These principles were refined in the musical treatises Natya Shastra, by Bharata (2nd–3rd century CE), and Dattilam (3rd–4th century CE).

- In medieval times, the melodic systems were fused with ideas from Persian music, particularly through the influence of Sufi composers like Amir Khusro, and later in the Moghul courts.

- Noted composers such as Tansen (sometimes called the father of modern Hindustani classical music) flourished, along with religious groups like the Vaishnavites.

- Tansen was composer in Persian, Turkish, Arabic, as well as Braj Bhasha, he is credited with systematizing many aspects of Hindustani music, and also introducing several ragas such as Yaman Kalyan, Zeelaf and Sarpada.

- He created the qawwali genre, which fuses Persian melody and beat on a dhrupad like structure. A number of instruments (such as the sitar and tabla) were also introduced in his time.

- At the royal house of Gwalior, Raja Mansingh Tomar (1486–1516 CE) also participated in the shift from Sanskrit to the local idiom (Hindi) as the language for classical songs.

- He himself penned several volumes of compositions on religious and secular themes, and was also responsible for the major compilation, the Mankutuhal (“Book of Curiosity”), which outlined the major forms of music prevalent at the time.

- In particular, the musical form known as dhrupad saw considerable development in his court and remained a strong point of the Gwalior gharana for many centuries.

- Much of the musical forms innovated by these pioneers merged with the Hindu tradition, composed in the popular language of the people (as opposed to Sanskrit) in the work of composers like Kabir or Nanak.

- This can be seen as part of a larger Bhakti tradition, (strongly related to the Vaishnavite movement) which remained influential across several centuries; notable figures include Jayadeva(11th century), Vidyapati (fl. 1375 CE), Chandidas (14th–15th century), and Meerabai (1555–1603 CE).

- After the dissolution of the Mughal empire, the patronage of music continued in smaller princely kingdoms like Lucknow, Patiala, and Banaras, giving rise to the diversity of styles that is today known as gharanas.

- Many musician families obtained large grants of land which made them self-sufficient, at least for a few generations (e.g. the Sham Chaurasia gharana). Meanwhile the Bhakti and Sufitraditions continued to develop and interact with the different gharanas and groups.

What are the similarities and differences between ‘Hindustani’ and ‘Carnatic’ music:

- Carnatic music and Hindustani music are two kinds of music traditions in India that show some important differences between them when it comes to the nature of singing, style of singing and the techniques involved in them.

- Carnatic music is said to have originated in the south India. On the other hand Hindustani music is said to have originated in several parts of northern and western India in different times.

- Both the styles are monophonic, follow a melodic line and employ a drone (tanpura) with the help of one or two notes against the melody.

Tanpura - Both the styles use definite scales to define a raga but the Carnatic Style employs Shrutis or semitones to create a Raga and thus have many more Ragas than the Hindustani style.

- Carnatic ragas differ from Hindustani ragas. The number of ragas used in Carnatic music is more when compared to the fewer ragas used in Hindustani music.

- The names of ragas are also different. However, there are some ragas which have the same scale as Hindustani ragas but have different names; such as Hindolam and Malkauns, Shankarabharanam and Bilawal.

- There is a third category of ragas like Hamsadhwani, Charukeshi, Kalavati etc. which are essentially Carnatic Ragas.

- They share the same name, the same scale (same set of notes) but can be rendered in the two distinctively different Carnatic and Hindustani styles.

- Unlike Hindustani music, Carnatic music does not adhere to Time or Samay concepts and instead of Thaats, Carnatic music follows the Melakarta concept.

- While Carnatic music is sung and performed in only one style, there are various styles of singing and performing in Hindustani music. Each style of school is called a ‘gharana’.

- Both the types of music differ in terms of the instruments used in the playing of music as well. While both types of music use instruments such as violin and flute, Hindustani music extensively employs the use of Tabla (a kind of drum or a percussion instrument), Sarangi (a stringed instrument), Santoor, Sitar, Clarionet.

- On the other hand Carnatic music extensively employs the use of musical instruments such as Veena (a stringed instrument), Mridangam (a percussion instrument), Gottuvadyam, Mandolin, Violin, Flute, Jalatarangam and the like.

- Ragam, talam and pallavi form the crux of the raga exposition in Carnatic music. Raga elaboration is given primary importance in Hindustani music. There is a perfect blend of both these types of music in top music festivals of India.

Principles of Hindustani music:

- The rhythmic organization is based on rhythmic patterns called tala.

- The melodic foundations are called ragas.(Each Raga has its own scale consisting of minimum five and maximum seven notes (swaras).

- A raga has specific ascending (Aaroh) and descending (Avaroh) movements).

- Ragas are used in semi-classical and light music as well.

- One possible classification of ragas is into “melodic modes” or “parent scales”, known as thaats, under which most ragas can be classified based on the notes they use.

- Thaats may consist of up to seven scale degrees, or swara. Hindustani musicians name these pitches using a system called Sargam,

- The fine intonational differences between different instances of the same swara are called srutis. (it is considered the smallest interval of pitch that the human ear can detect)

- Alap: a rhythmically free improvisation on the rules for the raga in order to give life to the raga and flesh out its characteristics.

- The alap is followed by a long slow-tempo improvisation in vocal music, or by the jod and jhala in instrumental music.

- Bandish or Gat is a fixed, melodic composition set in a specific raga, performed with rhythmic accompaniment by a tabla or pakhavaj.

Types of compositions:

- The major vocal forms or styles associated with Hindustani classical music are dhrupad, khyal,and tarana. Other forms include dhamar, trivat, chaiti, kajari, tappa, tap-khyal,ashtapadis, thumri, dadra, ghazal and bhajan; these are folk or semi-classical or light classical styles, as they often do not adhere to the rigorous rules of classical music.

(1) Dhrupad

- Dhrupad is an old style of singing, traditionally performed by male singers.

- It is performed with a tambura and a pakhawaj as instrumental accompaniments.

- The lyrics, some of which were written in Sanskrit centuries ago, are presently often sung in brajbhasha, a medieval form of North and East Indian languages that was spoken in Eastern India.

- The rudra veena, an ancient string instrument, is used in instrumental music in dhrupad.

- Dhrupad music is primarily devotional in theme and content.

- It contains recitals in praise of particular deities. Dhrupad compositions begin with a relatively long and acyclic alap.

- The great Indian musician Tansen sang in the dhrupad style.

- A lighter form of dhrupad, called dhamar, is sung primarily during the festival of Holi.

- Dhrupad was the main form of northern Indian classical music until two centuries ago, when it gave way to the somewhat less austere khyal, a more free-form style of singing. Since losing its main patrons among the royalty in Indian princely states, dhrupad risked becoming extinct in the first half of the twentieth century.

- Some of the best known vocalists who sing in the Dhrupad style are the members of the Dagar lineage.Leading vocalists outside the Dagar lineage include the Mallik family of Darbhanga tradition of musicians.

- A section of dhrupad singers of Delhi Gharana from Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s court migrated to Bettiah under the patronage of the Bettiah Raj, giving rise to the Bettiah Gharana.

- Bishnupur Gharana, based in West Bengal, is a key school that has been propagating this style of singing since Mughal times.

(2) Khyal

- Khayal is a form of rendering a raga.The essential component of a khayal is a composition (Bandish) and the expansion of the text of the composition within the framework of the raga.

- Khyal is a Hindustani form of vocal music, adopted from medieval Persian music and based on Dhrupad. Khyal, literally meaning “thought” or “imagination”, is unusual as it is based on improvising and expressing emotion.

- Hindustani Music is much similar to Persian and Arabic music since all 3 genres are modal systems where the emphasis is on melody and not harmony. A Khyal is a two- to eight-line lyric set to a melody.

- Khyals are also popular for depicting the emotions between two lovers, situations of ethological significance in Hinduism and Islam, or other situations evoking intense feelings.

- Khyal contains a greater variety embellishments and ornamentations compared to dhrupad. Khyal’s romanticism has led to it becoming to most popular genre of Hindustani classical music.

- The singer improvises and finds inspiration within the raga to depict the Khyal.

- Although it is accepted that this style was based on Dhrupad and influenced by Persian music.

- Many argue that Amir Khusrau created the style in the late 16th century.

- This form was popularized by Mughal Emperor Mohammad Shah, through his court musicians.

- The compositions by the court musician Sadarang in the court of Muhammad Shah bear a closer affinity to the modern khyal.

- Some well-known composers of this period were Sadarang, Adarang, and Manrang.

What are the differences between Dhrupad and Khayal?

- Dhruvapada or Dhrupad is another form of rendering a raga.

- It has a specific composition, consisting of four parts and is sung in different styles.

- The percussion accompaniment is the Mridang or Pakhawaj, a one-piece drum, as opposed to the two-piece drum, the tabla in khayal.

- The main difference between these two musical forms is that the Dhrupad is rigidly bound by the composition and the tala, within which all improvisation has to be made.

- The Khayal, on the other hand, has the freedom to free itself from the rhythmic beat and then return to the beginning of each time cycle (tala).

- Also, the two essential idioms used in Khayal, which are absent in Dhrupad, are the Sargam and Taan.

- Sargam is the singing of the notes (sa, re, ga,..), per se, instead of words while Taan is the sequential movement through the different notes using the vowel “Aa”.

(3) Tarana

- Another vocal form, taranas are medium- to fast-paced songs that are used to convey a mood of elation and are usually performed towards the end of a concert.

- They consist of a few lines of poetry with soft syllables or bols set to a tune.

- The tillana of Carnatic music is based on the tarana, although the former is primarily associated with dance.

(4) Tappa

- Tappa is a form of Indian semi-classical vocal music whose specialty is its rolling pace based on fast, subtle, knotty construction.

- It originated from the folk songs of the camel riders of Punjab and was developed as a form of classical music by Shori Mian, a court singer for Asaf-Ud-Dowlah, the Nawab of Awadh.

(5) Thumri

- The Thumri is yet another form of rendering ragas. However , this very popular, light classical form of Hindustani music, is limited to specific ragas whose key emotion is lyricism and eroticism, e.g. Bhairavi, Gara, Pilu.

- Effective word-play usually characterizes a Thumri. Chiefly associated with folk songs of UP and Punjab, the Thumri is composed in dialects of Hindi.

- Thumri is a semi-classical vocal form said to have begun in Uttar Pradesh with the court of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, (r. 1847–1856).

- There are three types of thumri: poorab ang, Lucknavi and Punjabi thumri.

- The lyrics are typically in a proto-Hindi language called Brij Bhasha and are usually romantic.

(6) Ghazal

- Ghazal is an originally Persian form of poetry. In the Indian sub-continent, Ghazal became the most common form of poetry in the Urdu language and was popularized by classical poets like Mir Taqi Mir, Ghalib, Daagh, Zauq and Sauda amongst the North Indian literary elite.

- Vocal music set to this mode of poetry is popular with multiple variations across Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia, Turkey, India, Pakistan etc.

- Ghazal exists in multiple variations, including semi-classical, folk and pop forms.

![[Topic wise IAS Medieval Indian History Question Bank (1979-2015)]: (3) The Thirteenth Century](https://selfstudyhistory.com/wp-content/themes/daily-insight/assets/uploads/no-featured-image-500x375.jpg)

How do I cite this for a paper I am writing? Who is the author I can cite?